This is a page for a course, “Some Versions of Hamlet.”

This is a page for a course, “Some Versions of Hamlet.”

(Last updated 2/1/2023)

Hamlet is so complex and ambiguous that every reading of the text and every performance of it can constitute not just a different interpretation but essentially a different version of the play. This course examines the different “versions” of the character Hamlet and of his play as a whole in four ways: first, through reading of a “basic” text; second, through a study of the three main versions of Shakespeare’s text that have come down to us (the First and Second Quarto and the First Folio); third, through actors’ interpretations of Shakespeare’s creation on stage and on film; and fourth, through other authors’ renditions of the characters and events in the play, both before and after Shakespeare.

Selected Bibliography, including bibliographies, editions, specific studies, and a list of films and other literary versions of the story.

Hamlet Haven: An Online Annotated Bibliography

Textual Material

- Online Texts of the First and Second Quartos and the First Folio, edited by David Bevington for the University of Victoria, Canada.

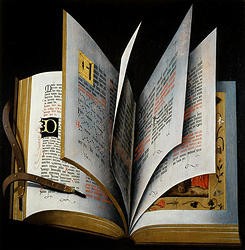

- The Enfolded Hamlet, Bernice Kliman’s compilation of the Second Quarto and the First Folio, similar to The Three-Text Hamlet, by Kliman and Bertram, but without the so-called “Bad Quarto.” You can read Q2 and F1 together as a composite, color-coded text or separately as individual texts. Kliman also supplies a list of variants for each version separate from the texts themselves (“Q2 Only” and “F1 Only”). For a different introduction to an updated page, click here.

- “The Relation Between the Second Quarto and the Folio Text of Hamlet”, an essay by Harold Jenkins, editor of The Arden Shakespeare, originally published in Studies in Bibliography, Volume 7 (1955): 69-83.

- Treasures in Full: Shakespeare in Quarto, graphic files of “the British Library’s 93 copies of the 21 plays by Shakespeare printed in quarto before the theatres were closed in 1642,” along with background information and analysis of how the texts were changed after the theaters reopened in 1660.

- Saxo Grammaticus, the complete Historica Danica, also referred to as the Gesta Danorum, of Saxo the Learned, in English translation by Oliver Elton, part of Douglas B. Killings’s Online Medieval and Classical Library. This is the oldest surviving version of the story of Hamlet (here “Amleth”). The Amleth portions of Saxo’s story are in Book Three and Book Four. You can also read an edited translation of the Amleth portions alone in a translation by Professor Emeritus D. L. Ashliman of the University of Pittsburgh here (be aware that there are a few potentially confusing typographical errors, including inconsistent spellings of characters’ names).

- Belleforest’s Hamblet, the 1608 English translation of the Hamlet portions of Belleforest’s Histoires Tragiques. This text seems to have been scanned with highly unreliable OCR software, so it is full of errors that sometimes make nonsense of the text, but it is currently the only online version available. (Archived)

Hamlet in Performance

- The Stage History of Hamlet, from the program of a 1995 production of the play by George Dillon with 7 actors, 2 musicians and a talking dog.

- Shakespeare and the Players: Hamlet An illustrated history of the actors who have portrayed Hamlet and other characters since the late nineteenth century, by Prof. Harry Rusche of Emory University.

- Paintings of Scenes from Hamlet from the web site Shakespeare Illustrated, by Prof. Harry Rusche of Emory University.

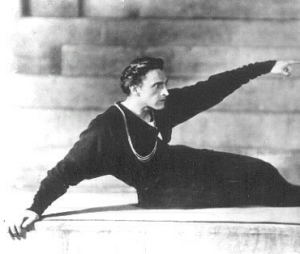

- “On Seeing Madame Bernhardt’s Hamlet”, a contemporary review by Elizabeth Robins, originally published in North American Review 171 (December 1900), 908-919. (Archived)

- John Barrymore, Shakespearean Actor Photographs of Barrymore, his predecessors and successors, many in Shakespearean costume, including several as Hamlet.

- Seventeen Ways of Looking at Hamlet A compilation of seventeen short reviews of Michael Kahn’s production at the Shakespeare Theatre in Washington, D.C., in the Fall of 1992. Reviews are by members of the Languages of Performance Institute.

- “A Live Wire to the Brain: Hooking Up Hamlet“, an article by Michael Almereyda, first published in The New York Times, about his conception of Hamlet for his 2000 film.

- The Hamlet Project: Prison Performing Arts, a web site for a program in the St. Louis penal system in which artistic director Agnes Wilcox produced Hamlet with prison inmates, one act at a time over a period of three years. The site includes reviews and reflections on the production, as well as an episode of the NPR show “This American Life” on the final year of the project, Act V. “Crime is easy; Shakespeare is hard.” Danny, Actor, The Hamlet Project.

- Two productions of Hamlet that use lines from the First “Bad” Quarto, as well as the usual Second Quarto and First Folio texts: A 1999 production directed by Joe Banno with four Hamlets–the main Hamlet character, plus his three alter-egos, Eye, Tongue, and Sword (from Ophelia’s line Act 3.1.151: “The courtier’s, soldier’s, scholar’s, eye, tongue, sword”). Eye, Tongue, and Sword comment on various things Hamlet says in his soliloquies. When he says, “Oh, what a rogue and peasant slave am I,” the always-angry Sword blurts out the First Quarto version, “Oh, what a dunghill idiot slave am I!” Here is the link to the Folger’s page for the production, and here is a link to a review in The Washington Post. A recent opera of Hamlet by composer Brett Dean and librettist Matthew Jocelyn that premiered at the Metropolitan Opera in 2022 also plays with all three foundational versions in interesting ways. Here is an interview with Dean and Jocelyn about how they used the texts to create something new.

General Sites for Shakespeare and Hamlet

- Hamlet Online, a hub site for Hamlet web pages, including history and analytical essays.

- Interpretation and Performances of Hamlet, from The Norton Shakespeare Workshop CD-ROM, edited by Mark Rose (Archived)

- Introduction to Hamlet, by three professors at the University of Liège, Michel Delville, Pierre Michel, and Eriks Uskalis (in French and English).

- Hamlet on the Ramparts, an excellent site from M.I.T. that focuses on Act 1, Scenes 4 and 5, Hamlet’s confrontation with the Ghost.

- Shakespeare and His Critics, a collection of 19th-century essays, many of which are on Hamlet, including works by Hazlitt and Coleridge, and a letter about Ophelia by Helena Faucit, who played the part with Macready. (Archived)

- “Multiplicity of Meaning in the Last Moments of Hamlet”, a paper for a symposium on paranoia in 1992 by John Russell Brown, published in the journal Connotations, which led to a rebuttal by Maurice Charney. (Archived)

- Hamlet: The Undiscovered Country This is a commercial site advertising Steve Roth’s book, which addresses many of the controversies surrounding Hamlet (was he mad? how old is he?) and which is aimed at the intelligent reader who is not an expert. This is not an endorsement of any of the ideas in the book, but this is a useful site with the book’s entire first chapter and very good links to other Hamlet sites.

- Titles from Hamlet, a list of literary titles that contain references to Hamlet or from quotations in the play.

You must be logged in to post a comment.